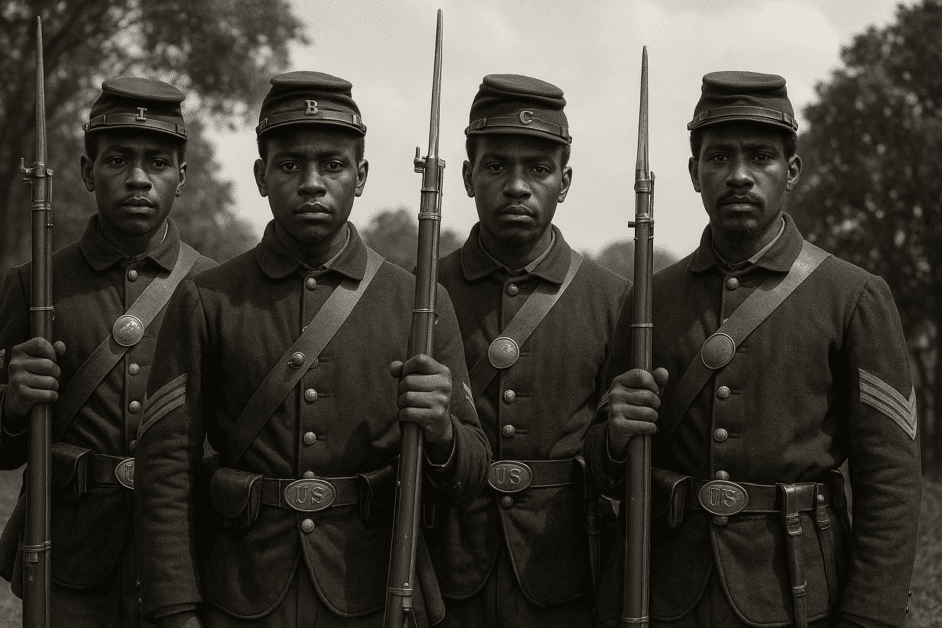

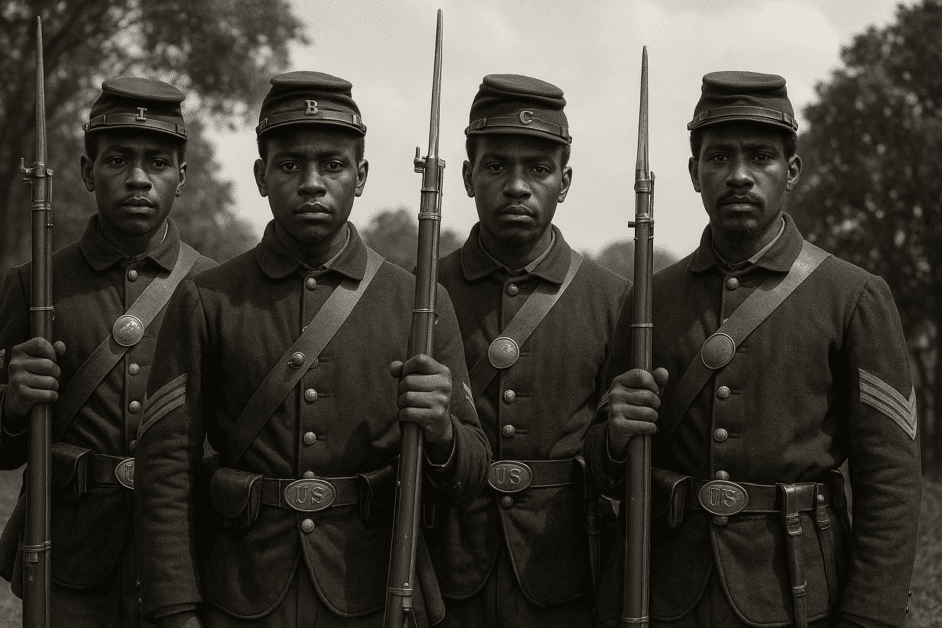

Memorial Day Was Black-Led Celebration Of Freedom That Racism Tried To Erase

Charleston’s Forgotten Memorial Day Roots Were Planted by Black Hands Honoring the Union Dead

Memorial Day might look like backyard barbecues and flag-draped parades now, but its earliest roots trace back to the ruins of the Civil War. And it all started with newly freed Black people who insisted the Union’s fallen be appropriately honored.

On May 1, 1865, just weeks after the Civil War ended, about 10,000 Black residents of Charleston, South Carolina, gathered at a former Confederate racetrack.

At this location, hundreds of Union soldiers had died and been buried in unmarked graves. The site had been a prison camp during the war. Over 257 Union troops, most succumbing to disease, were dumped into shallow pits behind the track.

Instead of letting those soldiers tumble into obscurity, a group of roughly two dozen Black people stepped in to ensure they were remembered. Believe it or not, they exhumed the bodies, laid them in organized rows and built a 10-foot-high white fence. The arch read “Martyrs of the Race Course” in black paint.

The tribute was no quiet affair.

It began with 3,000 Black schoolchildren marching around the graves with flowers, singing “John Brown’s Body.” Behind them came Black women and men representing various societies, pastors preaching sermons and about 30 speakers. It was organized by James Redpath, the Scottish immigrant, journalist and anti-slavery activist. Union regiments, both white and African Americans, drilled and paraded around the freshly laid graves. The entire day was filled with song, prayer and remembrance.

The Charleston Daily Courier and the New York Tribune reported on the event. The graves looked like “one mass of flowers,” per the Courier. The Tribune called it “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

After finding a Tribune article in a Harvard archive, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Blight uncovered this largely forgotten story in 1996. His book, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, argues that this Memorial Day predecessor was buried—pun intended—because it didn’t fit the narrative white historians wanted to tell.

In the decades after, Southern organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and other racist groups denied knowledge of the event or shifted credit to white figures like Redpath. A 1937 book falsely claimed the ceremony occurred on May 30, the day General John A. Logan later designated as the official date for what would become Memorial Day in 1868.

Eventually, the Charleston racecourse was renamed Hampton Park after Confederate General Wade Hampton and the graves were moved to Beaufort National Cemetery. The memory of the Black organizers was all but erased.

But the truth still stands and will continue to be repeated. Before the government declared a national holiday and before white veterans made it official, Black Americans in Charleston created the first large-scale tribute to dead soldiers. They understood that freedom wasn’t free and simply wanted to thank them.

That Memorial Day story didn’t just honor the dead. It foreshadowed the centuries-long battle for recognition in the midst of racist erasure. This continues today.